Tiny Technology to Treat Big Brain Bleeds: The Explosion of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization

“It’s not a sexy problem, but a prevalent one.” This quote from Dr. Jason Davies, an endovascular neurosurgeon in Buffalo, NY and lead author of the Embolization of the Middle Meningeal Artery with Onyx Liquid Embolic System in the Treatment of Subacute and Chronic Subdural Hematoma (EMBOLISE) trial, sums up many neurosurgeons’ thoughts about chronic subdural hematomas (cSDH).

A cSDH is a persistent collection of blood, fluid and inflamed membranes underneath the thick, leather covering of the brain—the dura—but above the brain’s surface. Patients with cSDH can suffer symptoms such as headaches, memory loss, balance issues, personality changes, and cognitive difficulties. Still others may have more severe symptoms such as seizures, loss of consciousness, or even death. As Dr. Davies indicated, cSDH are prevalent, affecting millions worldwide—and that number is expected to rise.1

Many neurosurgical diseases, such as aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations and deep-seated brain tumors, require treatment with intricate surgeries and advanced technology. Brain bleeds, such as cSDH, in contrast, have historically been treated with less flashy methods, such as twisting holes in the skull with a drill, or removing part of the skull to drain the stagnant, inflamed concoction of blood and fluid.

Despite their simplicity, these traditional methods effectively remove the cSDH, which is why they’ve been used for thousands of years. However, cSDH tend to be stubborn—up to 30% will recur at least once, even after surgery. In many cases, this mandates an additional trip to the operating room which places the patient at risk for harm from an added operation, and of course, costs more money. Furthermore, many patients with cSDH—typically older patients—have other medical problems which make additional trips to the operating room even more undesirable.

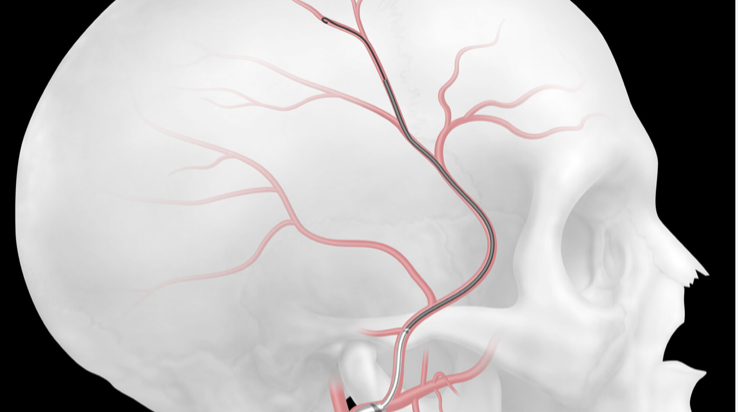

However, the paradigm is shifting. While cSDH has been viewed as "uninteresting," this perception is changing due to the enthusiasm surrounding a novel treatment called middle meningeal artery embolization (MMAe). Neurointerventionalists perform this procedure by employing tiny catheters and minute particles to block the middle meningeal artery (MMA)—an essential artery in the brain believed to contribute to the high rate of cSDH recurrence. The recent influx of compelling clinical evidence has prompted physicians to swiftly alter their approach to treating cSDH.

What is middle meningeal artery embolization and how does it work?

The story of MMAe began in the early 2000s when a group of Japanese neurointerventionalists published two reports comprising four patients with cSDH.2,3 Despite draining the cSDH with surgery, the authors noticed that the hematomas continued to recur with time. During the initial surgery, they also noticed that the hematoma was covered by an inflamed, vascularized membrane that seemed to be fed by small branches of the MMA. The authors hypothesized that occluding the MMA and subsequently stopping the blood flow to the hematoma membranes could prevent the hematoma from recurring. Using image guidance, the authors guided small catheters up into the MMA. Once they positioned the catheters within the MMA, they injected tiny beads into the artery, causing blood flow to cease—a process called embolization. After the procedure, the authors noticed that the hematomas gradually began to resolve and did not return. Indeed, this indicated that MMAe represented a potentially novel treatment option for cSDH.

But the premise of this procedure seems paradoxical: Use tiny catheters and even smaller molecules to fix a relatively large brain bleed. How can this technology work?

The answer to this question lies within the underlying pathophysiology of cSDH, a process that has been underappreciated until recently. Blood can initially accumulate in the subdural space—the area between the brain's surface and the dura—resulting from the tearing of a vein that connects the skull's inner surface to the brain's surface. These veins, known as bridging veins, stretch with age as the brain shrinks and pulls away from the skull. As they stretch, these veins become more susceptible to tearing, making subdural bleeds more prevalent in older patients who experience minor injuries, such as falls.

But after the veins tear and the blood remains in the subdural space, an inflammatory process ensues: This process—fueled by blood from the MMA—results in the formation of “inflammatory membranes,” which have leaky, fragile, tiny vessels prone to bleeding. As they bleed, more blood collects, causing more inflammation. This results in a vicious cycle, so cSDH tends to recur.

Indeed, even Rudolf Virchow—the esteemed 19th-century German pathologist—described what we now refer to as subdural hematoma as “pachymeningitis hemorrhagica interna,” suggesting an inflammatory cause. In 1965, utilizing their understanding of the microscopic anatomy of the dura and their knowledge of treatment responses in patients with cSDH, Rowbotham and Little identified two distinct categories of subdural hematomas: the first is attributed to traumatic tearing of the bridging veins, where surgery proves effective. The second results from bleeding in fragile vessels on the inner layer of the dura, often triggering an inflammatory response, which increases the vessels' fragility, leading to more bleeding, and perpetuating the cycle. In the latter instance, they noted that surgery is ineffective as it does not address the underlying pathophysiology.

Despite these observations, the underlying pathophysiology of cSDH remained underappreciated for decades.

This is, until the apparent success of MMA in the 2000s prompted others to reconsider.

A trickle of evidence... followed by a flood

While the early cases of MMAe from Japan suggested a possible alternative for treating cSDH, the literature remained limited for the following decade.

Then came 2015: Five large, randomized clinical trials demonstrated the benefits of endovascular mechanical thrombectomy for treating acute ischemic stroke. I’ve discussed this in a previous blog, but the results of these trials unequivocally demonstrated the potential for endovascular procedures to change the game in neurovascular medicine. Consequently, many neurointerventionalists began to ask: What other neurovascular diseases can we treat with minimally invasive endovascular therapy?

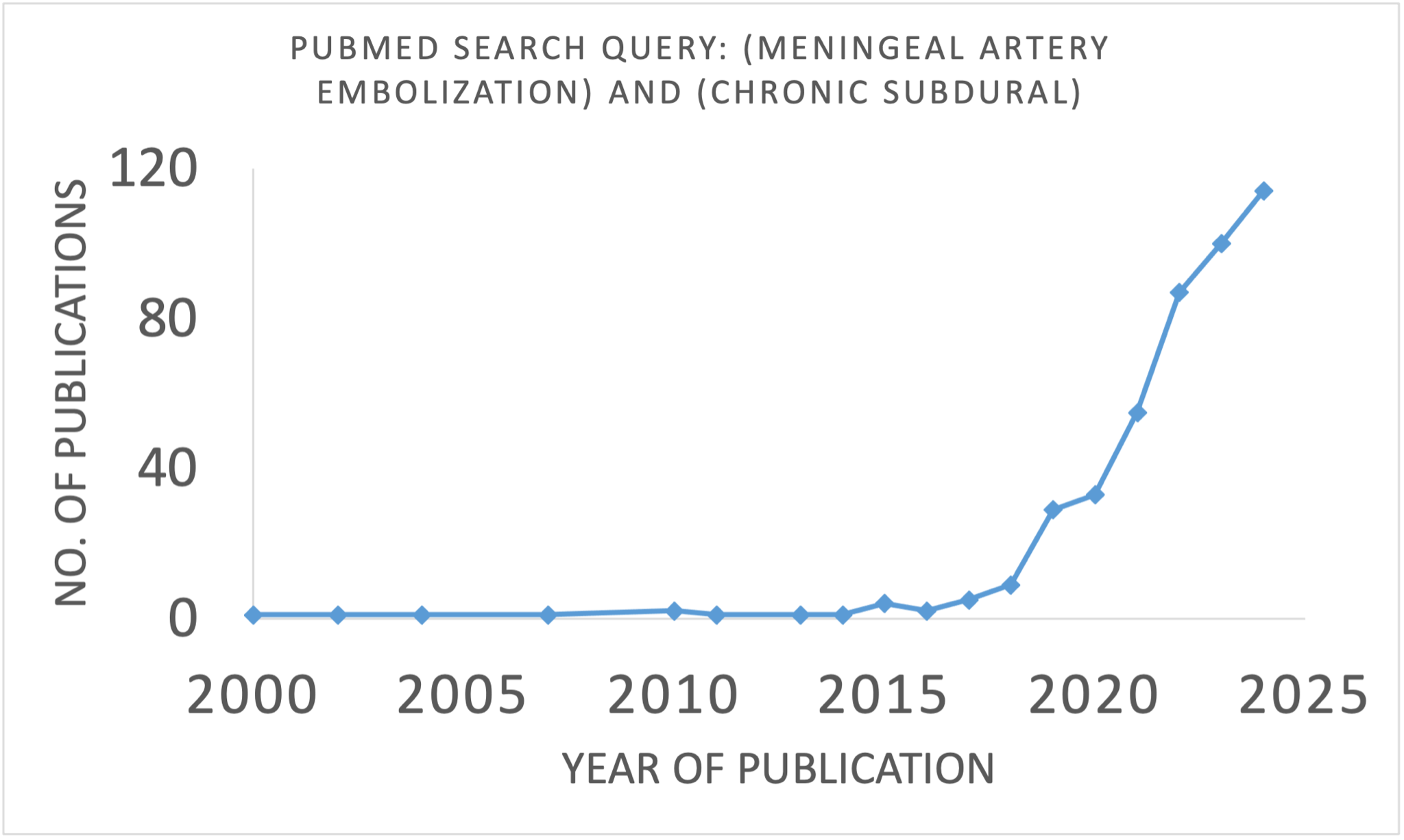

Drawing from Rowbotham and Little’s work, many began to explore the true pathophysiology behind cSDH, leading to the reclassification of the disease as a neurovascular condition rather than a traumatic one. Armed with this new understanding, numerous neurointerventionalists shifted their focus to MMAe. Indeed, within a few years of 2015, literature on MMAe for treating cSDH began to explode. I performed a very imprecise PubMed search to illustrate this in Figure 1.

This explosion was largely sparked by an observational study conducted by Ban et al., which demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of MMAe for cSDH.4 Since this pivotal publication, multiple large cohort studies and several meta-analyses have consistently shown the safety and clinical benefits of MMAe for cSDH. Up to that point, however, the evidence regarding MMAe had largely been limited to these observational studies. Despite the seemingly strong evidence for MMAe in treating cSDH, the necessity for a randomized clinical trial was clear to establish this method's effectiveness; indeed, such trials have begun in earnest in recent years.

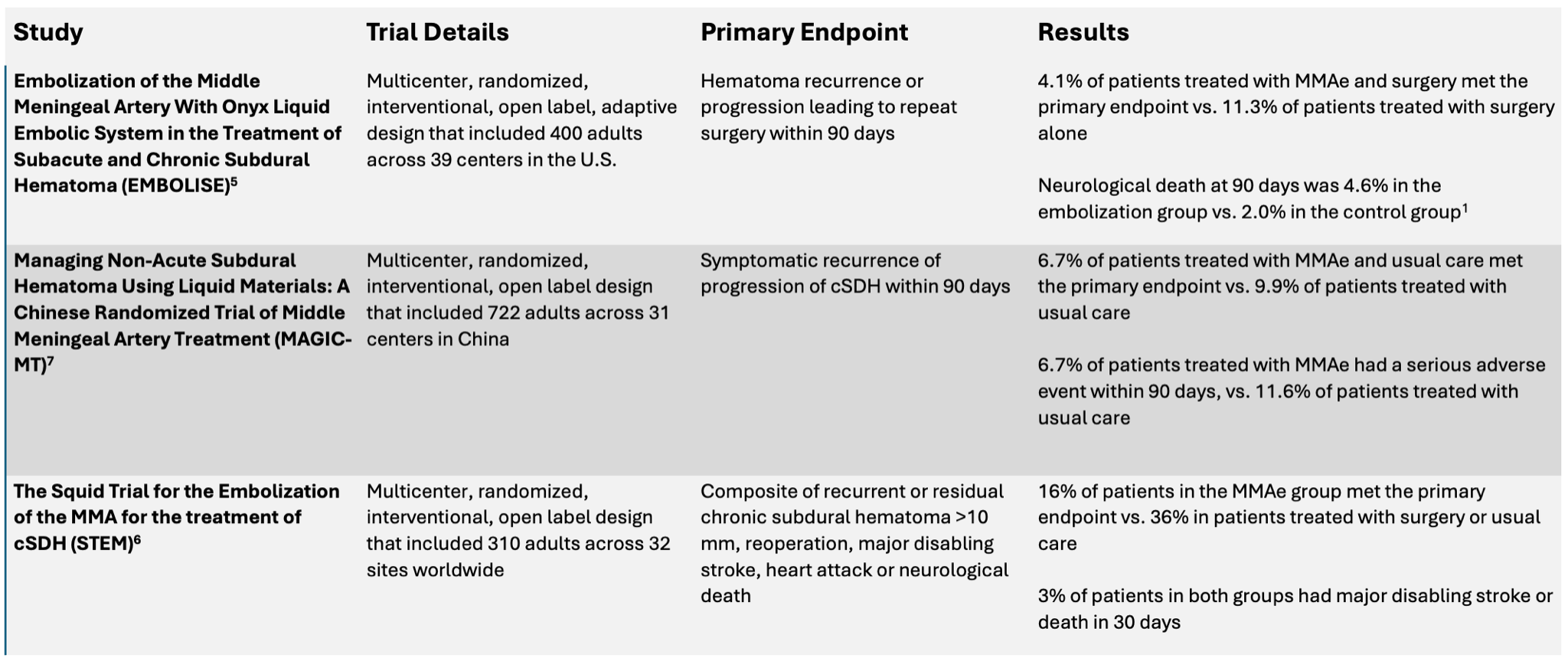

To date, three randomized clinical trials have available data reported at the International Stroke Conference (ISC) in February 2024 and have since been published (Table 1).5-7 In totality, these large, randomized clinical trials have produced concurrent evidence that MMAe using liquid embolics—a substance much like glue, which can occlude an artery—is a safe and effective method to prevent recurrence or progression of cSDH necessitating return to the operating room, particularly when used as an adjunctive to surgical intervention. Given these results, many neurointerventionalists have argued that MMAe should be integrated into the care pathway for patients with cSDH, particularly as an adjunct to surgical drainage.8

Table 1. Three randomized controlled trials presented at the International Stroke Conference in February, 2024 demonstrated a benefit of MMAe for preventing recurrence or progression of, or reoperation for cSDH. All three studies also showed an equivalent or superior safety profile of MMAe compared to standard care.

Questions remain

These three trials differ in terms of design and outcome measures. Nevertheless, the findings all point in the same direction, indicating yet another paradigm shift in neurovascular medicine. Many have suggested that the simultaneous reporting of these trials at ISC 2024 has flavors of mechanical thrombectomy in 2015.

Despite promising data from initial clinical trials, much work remains. Nearly a dozen additional clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the effectiveness of MMAe in treating cSDH, each with different study designs, outcome measures, and embolization materials. Several important questions remain, but I will highlight the two main ones.

First, the specific contexts in which MMAe should be used must be determined. Without a doubt, large, symptomatic cSDH will continue to require surgical drainage. As of now, MMAe appears to be an effective adjunct to surgery for preventing recurrence and return to the operating room. But whether or not MMAe can function effectively as a stand-alone procedure has yet to be determined. Some data indicate that it can treat smaller cSDH without surgical drainage. For example, the Squid Trial for the Embolization of the MMA for the treatment of cSDH (STEM) study found that their positive results were mainly driven by patients who underwent stand-alone MMAe compared to patients who were observed, with recurrence rates of 19% and 59% respectively, indicating that MMAe can indeed be effective in preventing recurrence without the need for concomitant surgery.6 The EMBOLISE trial has an independently powered observational arm in which a similar hypothesis is being tested, although these data have not yet been published.5 Indeed, forthcoming clinical trials seek to answer these critical questions. One such trial is the CHESS trial, which aims to understand if MMAe can be used instead of surgery for moderately sized cSDH.

Other essential questions regarding the context of MMAe for cSDH have also been posed: Is MMAe a safe and effective alternative for treating patients with cSDH who may not be able to undergo surgical drainage, such as those on anticoagulation? Can MMAe address bilateral cSDH? Are there particular “types” or “shapes” of cSDH that would benefit most from MMAe?

Second, it is unclear which product type is the safest and most effective for embolizing the MMA, and in which contexts it should be used. Products can be classified into coils, particles, or liquid embolics,9 however, limited evidence exists regarding which product may be best, though it is likely all three may be uniquely beneficial in certain circumstances. However, Onyx™, a liquid embolic from Medtronic, has been associated with lower rates of cSDH recurrence and complications compared to particles and coils.10 All three clinical trials in Table 1 utilized a liquid embolic as their product. Still, as more clinical trials that use various products come to fruition, future meta-analyses will provide more information about which products may be safer and more effective, and in which contexts.

Despite these lingering questions, enormous progress has been made in developing a new treatment for cSDH. While it may not be as glamorous as some other neurovascular diseases, cSDH is indeed common and will likely become even more so. For thousands of years, subdural bleeds have been managed through surgical drainage, and we are just beginning to understand how effective MMAe could be in treating this devastating condition, and industry leaders will undoubtedly soon begin introducing new endovascular technologies designed specifically for MMAe.

Despite the morbidity and mortality associated with cSDH, minimally invasive management of this disease is incredibly bright.

References

1. Neifert SN, Chaman EK, Hardigan T, et al. Increases in subdural hematoma with an aging population—the future of American cerebrovascular disease. World neurosurgery 2020;141:e166-e74.

2. Mandai S, Sakurai M, Matsumoto Y. Middle meningeal artery embolization for refractory chronic subdural hematoma: Case report. Journal of neurosurgery 2000;93:686-8.

3. Takahashi K, Muraoka K, Sugiura T, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for refractory chronic subdural hematoma: 3 case reports. No shinkei geka Neurological surgery 2002;30:535-9.

4. Ban SP, Hwang G, Byoun HS, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma. Radiology 2018;286:992-9.

5. Davies JM, Knopman J, Mokin M, et al. Adjunctive middle meningeal artery embolization for subdural hematoma. 2024.

6. Fiorella D, Monteith SJ, Hanel R, et al. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery for chronic subdural hematoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2024.

7. Liu J, Ni W, Zuo Q, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for nonacute subdural hematoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2024;391:1901-12.

8. Levitt MR, Hirsch JA, Chen M. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: an effective treatment with a bright future. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery 2024;16:329-30.

9. Tudor T, Capone S, Vivanco‐Suarez J, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a review of established and emerging embolic agents. Stroke: Vascular and Interventional Neurology 2024;4:e000906.

10. Ku J, Dmytriw AA, Essibayi M, et al. Embolic agent choice in middle meningeal artery embolization as primary or adjunct treatment for chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2023;44:297-302.

Post a comment