The Total REALITY Study and What it Means for Directional Atherectomy

As a third-year medical student, I had the opportunity to rotate through a vascular surgery service. The rotation revealed a strange duality: on one hand, the procedures and technology employed to treat patients with vascular diseases were remarkable. From complex, 12-hour bypass surgeries to using image guidance, wires, balloons, and other advanced interventional technologies to open narrowed or blocked arteries, I was fascinated by how advanced the field was.

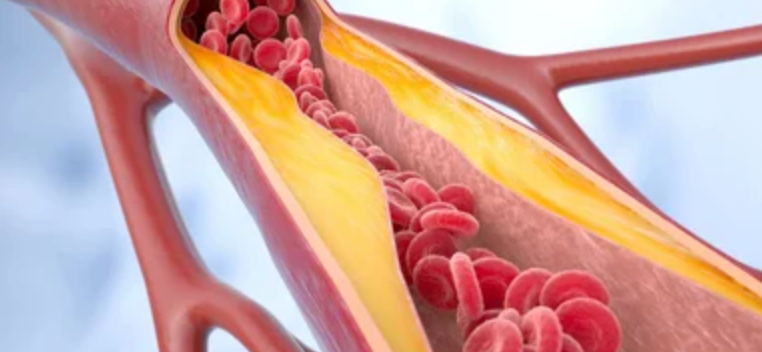

But on the other hand, it was difficult to see the suffering that peripheral artery disease (PAD) imposed on its victims. Many patients—such as those with blocked arteries in their legs—could hardly walk around their back yard. Still other patients with long-standing disease had lost several toes to amputation, and were at risk of losing their entire lower leg due to insufficient blood flow.

PAD affects over 200 million people worldwide, and that number is expected to rise.1 Traditionally, PAD has been treated with bypass procedures—surgical interventions that involve diverting blood past a narrowed artery by stitching in a graft. Despite the procedure's effectiveness, it carries several risks and is typically reserved for patients who have not responded to other therapies.

Since the advent of interventional radiology in recent decades, many patients are now treated with endovascular procedures, including stents, balloons, and other technologies to open narrowed arteries. These procedures are minimally invasive, effective, and have a lower risk of complications than bypass surgeries. Consequently, most patients with PAD who do not respond to medication or lifestyle changes will undergo an endovascular procedure to alleviate their symptoms.1,2

As endovascular procedures continue to gain popularity for treating PAD, many device companies have developed newer technologies to open narrowed arteries caused by plaque buildup. One such technology is directional atherectomy (DA), which employs tiny, cutting blades to “shave” and remove plaque inside an artery. This process contrasts with stenting, which involves permanently placing a metal mesh into the artery to push the plaque toward the artery's wall, thus allowing more blood to flow through. Furthermore, DA is believed to be more effective against “tougher" calcified plaques, and may be a more robust option to remove plaques that aren't amenable to treatment with other, less "mechanical" methods, such as laser atherectomy.

Currently, Medtronic’s HawkOne Atherectomy System™ is the leading player in this market.

Although DA appears to be an effective method for treating PAD, the literature lacks robust data from clinical trials comparing DA to other interventional methods. Consequently, it remains unclear how effective DA is in treating PAD and when it should be used for maximum benefit. Indeed, several key opinion leaders in the field have expressed this sentiment.

In November 2024, however, data from the Total REALITY study were presented at the Vascular InterVentional Advances (VIVA) conference in Las Vegas. These data provide new insights into how DA can be utilized in patients with PAD.

Let’s explore what Total REALITY is and what its findings signify.

What is Total REALITY?

One method for treating PAD involves using a balloon to reopen the artery—balloon angioplasty. Some balloons, known as drug-coated balloons (DCB), are coated with medication to reduce plaque regrowth. The DCB method has shown to be superior to other approaches for treating PAD and has become the treatment of choice for most patients.3 Sometimes, plaque is “prepared" through a separate treatment method before being subjected to a DCB. One preparation method is DA, while another, known as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), involves using a separate balloon to enlarge the narrowed vessel. This allows easier access for the DCB into the plaque and improves the penetration of the medication into the plaque tissue. It is believed that this “preparation” leads to more successful outcomes when treated with DCB.4

But is DA or PTA the most effective preparation method before DCB treatment?

By combining data from the VIVA REALITY5 study and the Total IN.PACT6 dataset, Total REALITY sought to answer this question. More specifically, Total REALITY conducted a propensity score-matched analysis to compare patients with PAD treated with DA and DBC against those treated with balloon dilation and DBC. The authors evaluated the following outcomes:

· Arterial patency after one year of follow-up

· Provisional stenting (that is, patients who required re-treatment with a stent)

· Major adverse events

What did the results show?

The most beautiful aspect of a randomized clinical trial is that the groups being compared are—at least theoretically—entirely equal at baseline. This is the magic of randomization. Without randomization—such as in retrospective observational studies—it can be challenging to ensure that the groups being compared do not differ before the treatment being tested. This is why many studies employ propensity score matching, a statistical method that “matches” patients between groups before the intervention, minimizing the risk of selection bias.

In the Total REALITY study, the results of the propensity score matching demonstrated equivalence between the compared groups being compared. There was, however, one crucial difference: the group treated with DA and DCB had a significantly higher percentage of patients with severe plaque calcification compared to the PTA and DCB groups (71.4% and 5.9%, respectively). This finding is crucial, and here’s why: the study found that the one-year patency of the affected artery did not differ between the groups, even though the DA and DCB group had more patients with severe calcification. With such severe calcification, one might expect this group to have a lower one-year patency; however, both groups were equivalent.

The study also found that the DA and DCB groups had a higher stent-free patency at one year, although this did not quite reach statistical significance. Additionally, the DA and DCB groups exhibited a statistically significant lower rate of provisional stenting at one year of follow-up. Finally, major adverse events, including amputation, thrombosis, or the need for surgical bypass, did not differ between the groups.

What do the results mean for DA?

The conclusions drawn from the Total REALITY data are straightforward: Overall, DA appears to be a safe and effective "preparation" method before DCB treatment. More specifically, both DA and DCB seem to be safe and particularly effective for improving patency and preventing permanent stent placement in complex PAD lesions that are highly calcified.

Indeed, these data suggest that DA plays a significant role in treating PAD despite the seemingly prevalent skepticism among field leaders.

What else is needed?

The Total REALITY study provides intriguing data that supports the use of DA in the context of DCB for treating PAD. Despite its strong methodology, it is not a clinical trial. Thus, the necessity for randomized clinical studies that directly compare DA with other interventional procedures is apparent.7 Several questions remain about the effectiveness of DA in specific contexts. While the Total REALITY study demonstrated its safety and effectiveness as a preparation method for DCB treatment, it's unknown how effective it is on its own for treating PAD.

Can it be an adjunct interventional method for other treatment methods besides DCB angioplasty? Does it improve drug delivery into plaque tissue vis-à-vis DCB, as many have hypothesized? Are there certain lesions that respond better to DA than others? What will data show from large-scale registries? How do patient-reported outcomes gel with clinical outcomes data?

Certainly, answers to these questions will help develop treatment algorithms and guideline statements.

Several leaders in interventional radiology and vascular surgery hope to answer these essential questions in the future. In the meantime, however, DA will certainly play a role in treating PAD.

References

1. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017;69:e71-e126.

2. Pinto P, Chaar CIO. Atherectomy–the options, the evidence, and when should it be used. Annals of Vascular Surgery 2024;107:127-35.

3. van den Berg JC. Drug-eluting balloons for treatment of SFA and popliteal disease–A review of current status. European journal of radiology 2017;91:106-15.

4. Konishi H, Habara M, Nasu K, et al. Impact of optimal preparation before drug-coated balloon dilatation for de novo lesion in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2022;35:91-5.

5. Rocha‐Singh KJ, Sachar R, DeRubertis BG, et al. Directional atherectomy before paclitaxel coated balloon angioplasty in complex femoropopliteal disease: the VIVA REALITY study. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2021;98:549-58.

6. Shishehbor MH, Schneider PA, Zeller T, et al. Total IN. PACT drug-coated balloon initiative reporting pooled imaging and propensity-matched cohorts. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2019;70:1177-91. e9.

7. Chowdhury M, Secemsky EA. Atherectomy vs other modalities for treatment during peripheral vascular intervention. Current Cardiology Reports 2022;24:869-77.

Post a comment